In June 1988 I joined the National Park Service’s Bandelier Archaeological Survey to document its work – an effort that produced my first book. It formalized a pattern of question-asking and answer-seeking that began in 1974 with a trip to Mexico and continued to 2023 – a pattern explained in my essay The Jaguar’s Teeth. In all my work, I tried to be creative, expressed in diverse formats but united by curiosity, concern, and a desire to tell an inspiring story.

My Work Falls Into Two Phases:

(1) A West That Works (1988-2005) (2) The Age of Consequences (2006-2023)

A WEST THAT WORKS: My work begins in the the American West, where I spent my formative years hiking the region’s trails, driving its freeways, investigating its ruins, and exploring its wide open spaces. Wanting to know more, I studied the West’s history, read its authors, and photographed its vistas. With the founding of the Quivira Coalition in 1997, I switched from an observer-interpreter of the West to an active participant on front line issues. I had anguished questions: How do we get beyond stereotypes? Why didn’t ranchers and environmentalists get along? How could we energize the radical center and reach across the urban-rural divide? Where could we heal damaged land and damaged relationships? My creative responses included photography, archaeology, activism, essays, column-writing, and the Quivira Coalition.

THE AGE OF CONSEQUENCES: In 2006, my work transitioned in response to the devastation caused by Hurricane Katrina. Climate change jumped onto my radar screen, shifting how I looked at the relationships between land, water, and people. My concerns became global and urgent. My anguished questions expanded: How do we build resilience in our land and communities? How can we strengthen local food systems? How can we best sequester carbon in soils? How do we scale-up regenerative agriculture? What other collaborative, nature-based solutions can address our multiplying challenges? My creative answers included book writing, a refocus of the Quivira Coalition’s mission and annual conference, a journal, a blog, lectures, photography, fiction, and co-authorship of four nonfiction books.

A WEST THAT WORKS

In the Land of the Delight-Makers: an Archaeological Survey in the American Westest

Documentary Photography Book with text 1988-89 (University of Utah Press 1992)

As I began to explore the West, I was struck by the power and persistence of shop-worn stereotypes and iconic imagery of the region. It wasn’t the West I knew. From personal experience, I suspected there were more archaeologists than cowboys at work. In the spring of 1988, I purchased a medium-format Bronica camera and began taking photos of the West from a different perspective. My inaugural project took me to the canyons of the Parajito Plateau in Bandelier National Monument, northern New Mexico.

“During the summers of 1988 and 1989, I had the opportunity to work with the National Park Service’s Bandelier National Monument Archaeological Survey as a photographer. Initially, I went into the field with the simple goal of capturing the spirit of the survey for the Park Service … I created this book with three goals in mind: first, to introduce a long-neglected aspect of archaeological fieldwork to the reading public; second, to contribute to the education of the archaeological enthusiast; and third, to place archaeologists in the larger context of the modern American West …” – from the Introduction

The Indelible West: Photographs 1988-1998

Foreword by Wallace Stegner

Fine Art Photography Book (published as an online book 2012)

This project was born on a summer day in 1988 while visiting my parents in Phoenix, Arizona. I was struck by a thought: in less than two years the American West would mark the centennial of the closing of its famous frontier. Photographing the modern frontier as a way of celebrating this landmark event would be an interesting project.

“The West as a place and a process created indelible impacts on our nation and continue to change us to this day, and will never stop doing so. The frontier is very much alive. That’s because the meeting-line between nature and culture, visible on the land and in its people, is constantly evolving and renewing itself. The photographs in this book are a snapshot of one moment in the frontier’s evolution, the intersection of a time and place now gone.” – from my Introduction (2012)

“What we have in Courtney White’s book is a recording of one passing phase of that frontier. And what a pleasure it is to see the real Wests captured in their flow! What a reassurance it is to see the Wests recorded in their living reality, instead of getting another view of someone being cut off at the pass in the Alabama Hills of the Kanab Desert, shooting wildly with both hands from guns that never need re-loading.” – Wallace Stegner from his Foreword (1992)

Read Wallace Stegner’s Foreword

Knowing Pecos: a Small History of a Big Place

History Book 1992-1995 (Dog Ear Press 2013)

For four seasons I worked as a documentary archaeologist at Pecos National Historical Park, located near Santa Fe. I kept a journal with the goal of writing a book about the tribulations of the national park idea in the modern world, a hot topic at the time. In the end, I wrote an admiring history of the park instead – and by extension a portrait of northern New Mexico, my new home.

“No other national park unit in the nation can tell the story of human history in North America as Pecos can; and no other park can do so with the aid of such an attractive landscape… Everywhere I went in the park, I ran into beauty and intrigue. Better yet, nearly every enchantment concealed a secret: the foundations of an abandoned home in a pasture, the remains of an old mill in a grove of river trees…We often joked that the whole park was one big archaeological site, and we were not far wrong. Beauty and history are interwoven at Pecos and their inseparability made every day an adventure…” – from my Introduction

Adobe Typology and Site Chronology: a Case Study From Pecos National Historical Park

Peer-reviewed Archaeological Research Paper 1996 (Kiva vol. 61, no. 4)

During my documentary work at Pecos, I noticed differences in the colors and shapes of the form-molded adobe bricks used in the Spanish colonial-era buildings. Working with Jake Ivey, a historian with the National Park Service, we embarked on a research project that eventually correlated multiple adobe and mortar types to the documented history of the 18th-century church and convento, solving stubborn riddles about its construction sequence. I subsequently wrote a paper and submitted it to Kiva, the Journal of Southwestern Anthropology and History.

“The correlation between the typology and the mission’s documented history was buttressed by botanical and geochemical analyses of adobe soils. It is likely that this method of research can be applied to other historic, and possibly prehistoric, sites with equally beneficial results.” – from the Abstract

Canyonlands

Two-Act Play 1995-1999

This play explores the conflict between ‘boomers’ and ‘stickers’ in the West at the start of the 21st century. It is set in a bicycle shop in a small town in southeastern Utah over the course of one summer. The shop’s presence has caused conflict between its owner, Joshua Rose, who recently arrived with his family from Los Angeles, and the last remaining farmer within town limits, who doesn’t like the changes taking place to his home. A plot twist halfway through the play turns everyone’s expectations upside down. And much like the town he has invaded, Joshua will never be the same again.

“This place has become so diverse nobody gets along anymore.” – a resident of Boulder, Utah, in a newspaper quote.

Grassroots: The Rise of the Radical Center

Three Columns: The Uneasy Chair; The Far Horizon; and The Next West 1995-2011 (Dog Ear Press 2016)

This book combines three columns that I wrote over sixteen years – the first for the Rio Grande Chapter of the Sierra Club; the second for the Quivira Coalition; and the last one for my web site. The first two columns chronicle the rise of collaborative conservation and regenerative agriculture in the Southwest from a front-line perspective; the third column explores the broken promise of the so-called New West.

The term radical center was coined by Bill McDonald, a rancher in southern Arizona and cofounder of the Malpai Borderlands Group, a pioneering collaboration between ranchers, conservationists, scientists, and public land managers. It describes a ‘third way’ beyond polarization, a grassroots convening of diverse people to discuss their common interests rather than argue their differences. The radical center means to work cooperatively on a pragmatic program of action that improves the well-being of all living things.

“In the American West during the 1990s, the daily news featured political gridlock, anti-government anger, Us vs. Them factionalism, political assaults on environmental regulations, local demands to turn over federal land to the states, ‘patriotic’ armed militia groups, courtroom brawls between urban and rural residents over endangered species, and a bunch of finger-pointing and trash-talking. Sounds like today!… If problems are cyclical so are solutions.” – from my Preface.

Invitation to Join the Radical Center (a declaration I cowrote in 2003)

The Quivira Coalition

Nonprofit Organization Cofounder and Executive Director 1997-2015

In 1997, I cofounded the Quivira Coalition with rancher Jim Winder and conservationist Barbara Johnson, both of whom I met in the Sierra Club (see Prologue to Revolution on the Range). Our original goal was to support an emerging ‘radical center’ among ranchers, conservationists, scientists and public land managers with a focus on cattle management, collaboration, riparian restoration, and improved land health. We called this approach The New Ranch. In 2007, we adjusted Quivira’s mission statement to reflect a rapidly changing world, particularly under climate change. It read: “to build resilience by fostering ecological, economic, and social health on western landscapes through education, innovation, collaboration, and progressive public and private land stewardship.”

Major projects during my time included: an Annual Conference; a ranch apprenticeship program; a major riparian restoration effort in northern New Mexico on behalf of the Rio Grande Cutthroat trout; a collaboration with the Ojo Encino Chapter of the Navajo Nation; a Grassbank; a cattle herd; a grassfed meat business; and the idea of a carbon ranch.

During my tenure as Executive Director, at least one million acres of rangeland, thirty linear miles of riparian drainages and 15,000 people directly benefited from the Quivira’s collaborative efforts. We worked closely with Bill Zeedyk to disseminate his innovative ideas on ecological restoration. We organized over one hundred educational events on topics as diverse as drought management, riparian restoration, fixing ranch roads, reading the landscape, monitoring, water harvesting, low-stress livestock handling, and grassfed beef. We published numerous newsletters, journals, bulletins, field guides, and books. I was the author of fifteen Annual Conferences, whose goals included giving science a platform; creating a space for diverse friendships; and sharing stories of success and hope.

Along with a handful of ranches, farms, and nonprofits at the time, the Quivira Coalition was a pioneering advocate and innovator for what is now called Regenerative Agriculture which has grown into a global movement for healthy soils, nutritious food, collaborative stewardship, ecological restoration, and nature-based solutions to climate change.

The New Ranch Handbook: In 2001, Quivira published one of the first science-based cases for progressive ranching, which was rather radical for the time. Reissued in 2013.

Of Land and Culture: Environmental Justice and Public Lands Ranching: published in 2001, this report called out the environmental movement for its neglect of culture and history.

New Agrarian Apprenticeship: In 2007, I started a ranch and farm apprenticeship through Quivira that has grown dramatically over the years and expanded across the West.

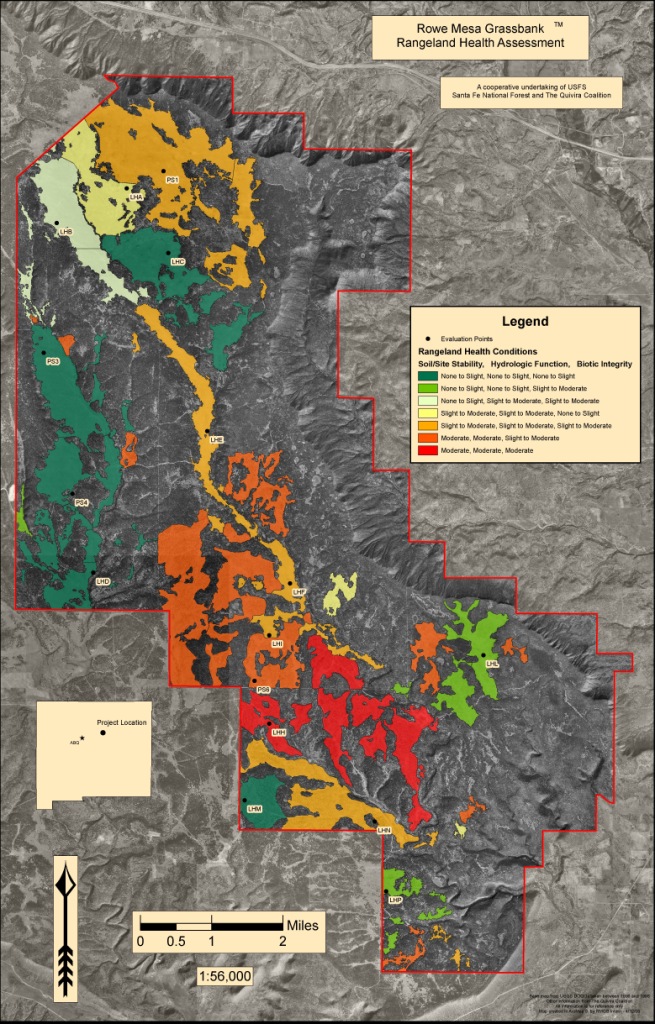

The Valle Grande Grassbank

Cattle Ranch Quivira Coalition 2004-2010

In 2004, the Quivira Coalition took over management of the Valle Grande Grassbank, a 36,000-acre ranch on U.S. Forest Service land near Santa Fe, New Mexico. The Grassbank was started by author Bill deBuys as an innovative model of a public-private partnership to restore ecological health while strengthening ranching traditions. Grassbanks were seen as a way to break bureaucratic gridlock that had paralyzed public lands. At one point, a dozen Grassbanks were in operation across the West. The Valle Grande Grassbank enabled Quivira to become cattle owners and produce grassfed meat for local sale. However, the Grassbank model had inherent financial challenges that proved difficult to overcome. For a variety of reasons, nearly every Grassbank called it quits. In 2010, we sold the ranch, ending our Grassbank experiment. Craig Conley and I wrote up a Summary of our experience and advice for the future in an essay titled Grassbank 2.0.

Bill deBuys’ article about Grassbanks, published in the Quivira newsletter (1998)

The flyer we produced for our grassfed meat

Mugido – my vision for public lands grazing, published in the Quivira newsletter (2006)

Let The Water Do The Work

Riparian Restoration Quivira Coalition 2001-2016

Of all the work that the Quivira Coalition did under my leadership, I am perhaps most proud of the support we gave Bill Zeedyk and his pioneering stream and wetland restoration methodologies. In the 1990s, ecological restoration was almost universally opposed by the environmental movement, which believed in a ‘hands-off’ approach to nature despite the degraded condition of many public and private lands. Quivira and Bill Zeedyk helped to change this attitude. Bill’s nature-based approach to restoration, which we implemented and promoted in numerous workshops, projects, publications, and presentations, proved to be highly effective and helped to set a wider stage for many other nature-based solutions to food, water, forestry, and climate challenges.

Thinking Like a Creek: an introductory profile of Bill that I wrote for our newsletter

The Gift: an article that I wrote for the journal Ecological Restoration in 2009

Bill Zeedyk’s presentation to Quivira’s Annual Conference in 2013

Building Resilience: Lessons from a Decade on Comanche Creek

Essays

Essays on the Radical Center, the New Ranch, the Carbon Ranch, and more 1998-2012

This is a compilation of essays written during my years at the Quivira Coalition for various publications, including Farming, Range, and Acres. Topics include: the radical center, collaborative conservation, grassbanks, ecological restoration, The New Ranch, carbon farming, land health, local food, agrarianism, and the Age of Consequences.

In 2005, I had the deep honor of having my essay “The Working Wilderness” published by Wendell Berry in his collection of essays titled The Way of Ignorance.

“I have asked Courtney to lend his essay to this collection for three reasons: First, I think it is a good essay. Second, it tells of a serious effort and continuing effort on the part of some ranchers and conservationists to develop local sufficient to to support a locally adapted land economy. This is an effort that is needed simply because it is necessary. If humans don’t learn to adapt their land economies to the nature of their places, that will be a disaster, first for their places and then for the humans. Third, it is an essay about cooperation between people and nature, between people and their places, and between ranchers and conservationists. This, again, is necessary…” – Wendell Berry

Read “The Working Wilderness” and Wendell Berry’s Introduction

Revolution on the Range: the Rise of a New Ranch in the American West

Collection of Profiles and Essays 2002-2006 (Island Press 2008)

‘While conventional wisdom told us compromise was impossible, a small group of ranchers and environmentalists crossed enemy lines for the sake of preserving the land they all deeply loved. And remarkable changes started to occur…Courtney White brings us the story of these peacemakers, including White himself, who began turning resentment, conflict, and suspicion into respect, cooperation, and trust. It is a powerful lesson in resolving environmental challenges, not just on the range but across the land.’ – Island P.

“As the grazing debate faded in the region and as hope began to grow alongside the wildflowers and bunch grasses, an answer to my anguished question began to reveal itself. We could get along, and in places did, especially where the dialogue started with soil, grass, and water. Peace, in other words, was possible.” – from my Prologue

“In a time when environmental reporting has become justifiably gloomy, this book is a refreshing breath of pragmatic optimism. White’s vision of stewardship, openness to new ideas, giving as well as taking, and flexibility will inspire anyone who loves humanity or the great outdoors.” – Publishers Weekly

Conservation for a New Generation: Redefining Natural Resource Management

edited by Richard L. Knight and Courtney White

Essays 2008 (Island Press 2009)

Colorado State University professor Rick Knight asked me to co-edit a volume of essays on the changing attitudes about resource management and conservation in the 21st century. In particular, he wanted to explore the rise of the collaborative conservation movement, the broadening of research and conservation paradigms to include working lands, and the increasingly urgent focus on ecosystem services, healthy food, and sustainability. In addition to my editorial duties, I contributed a chapter titled “Land Health: a Language to Describe the Common Ground Below Our Feet.”

“What conservation is today is highly debatable. What is not debatable is that effective conservation – today and in the future – will be different from what it has been. We need a vision that configures the changes into a pattern. Such a blueprint not only will provide guidance to agencies and organizations, but also will offer a conceptual and pragmatic road map for students, who are the future practitioners. Without such direction, it is certain that their education will prepare them for a time that has passed.” – Rick Knight, from his Introduction

Read my Essay (chapter Ten)

THE AGE OF CONSEQUENCES

The Age of Consequences: a Chronicle of Concern and Hope

Introduction by Wendell Berry

Collection of Essays 2002-2011 (Counterpoint Press 2015)

We live in what sustainability pioneer Wes Jackson calls “the most important moment in human history.” The various challenges confronting us are like a bright warning light in the dashboard of a speeding vehicle called Civilization, accompanied by an insistent buzzing sound. I called this moment the Age of Consequences – a time when the worrying consequences of our hard partying over the past sixty years have begun to raise anguished questions. The book is a series of essays that blend headlines with personal narrative and observation, travel, research, and hopeful answers.

“White strikes a refreshing tone that will resonate with readers turned off by the superior or condescending attitudes of some environmentalist writers…Throughout, he balances abstract questions and ideas with tangible life experiences…Readers will be engaged by his frank and thoughtful discussion of our modern environment.” – Kirkus Review

Read Wendell Berry’s Introduction

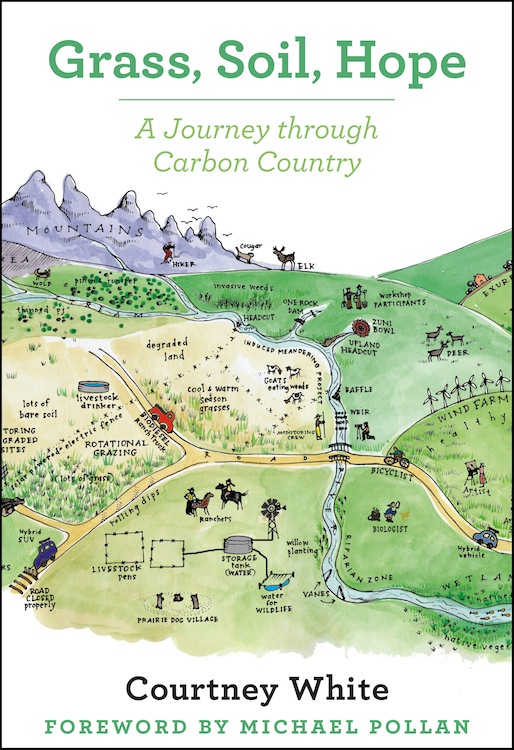

Grass, Soil, Hope: a Journey through Carbon Country

Nonfiction Book 2010-2013 (Chelsea Green 2014)

Right now, the only possibility of large-scale removal of greenhouse gases from the atmosphere is through plant photosynthesis and related land-based carbon sequestration activities. These include a range of already proven practices: composting, no-till farming, climate-friendly livestock practices, conserving natural habitat, restoring degraded watersheds and rangelands, increasing biodiversity, and producing local food. Grass, Soil, Hope takes readers on an entertaining journey on how all these practical strategies can be bundled together into an economic and ecological whole.

“Hope in a book about the environmental challenges we face in the 21st century is an audacious thing to promise, so I’m pleased to report that Courtney White delivers on it. He has written a stirringly hopeful book.” – Michael Pollan, from the Foreword

Read Michael Pollan’s Foreword

Read My Prologue

The Story of Carbon

A Blog 2012-2016

I wrote a blog from 2012 until 2016 on carbon, an amazing element that profoundly affects every facet of our lives. My principle goal was to explore the role soil carbon plays in regenerative agriculture and its potential to sequester atmospheric carbon dioxide, but I quickly learned it has so many other values as well. Carbon is fundamental to life – and it’s a lot of fun too! I compiled the blog into a single document and offer it to readers in hopes you’ll come to appreciate this incredible element as much as I did.

Thinking Outside the Holocene: Paul Gauguin’s Question and Aldo Leopold’s Answer

Lecture 2012

This is a video of a lecture I gave at the Quivira Coalition’s 11th Annual Conference in 2012, which explored human origins, motivations, and future challenges. It is a talk provoked by Paul Gauguin’s famous painting on these topics and resolved (partially) by Aldo Leopold’s experiences and writings. I tried to express my hopeful feelings about the challenges we face during This Moment In Time.

Two Percent Solutions for the Planet: 50 Low-Cost, Low-Tech, Nature-Based Practices for Combating Hunger, Drought and Climate Change

Nonfiction book 2013-2015 (Chelsea Green)

This book profiles fifty innovative practices that soak up carbon dioxide in soils, reduce energy use, sustainably intensify food production, and increase water quality and quantity. Why “two percent”? It is an illustrative number meant to stimulate our imaginations. It refers to: the amount of new carbon in the soil needed to reap a wide variety of ecological and economic benefits; the percentage of the nation’s population who are farmers and ranchers; and the low financial cost needed to get this work done. Using photographs, graphics and short essays, the book is a great introduction.

“This book is Courtney White’s most important work. It is the best practical guide to how we can begin to address the significant, unavoidable challenges awaiting us in our not-too-distant future. It inspires us to address these challenges creatively, especially with respect to our food and agriculture future, and to do it in cooperation with nature in ways that also heal the planet.” – Frederick Kirschenmann, Cultivating an Ecological Conscience

Grass, Soil, Hope: Regenerative Solutions for Changing Times

Lecture 2017

This is a video of the presentation I gave as the Keynote speaker at the American Forage and Grassland Council’s Annual Meeting in Roanoke, VA, on January 24, 2017. It was my second-to-last public presentation and the final version of a talk that I gave many times over fifteen years, tracing my journey as an activist and the evolution of the Quivira Coalition from its founding in 1997. Topics include: collaborative conservation, land health, the radical center, ecological restoration, thinking like a creek, ranching, grassbanks, carbon sequestration, and nature-based solutions for climate change.

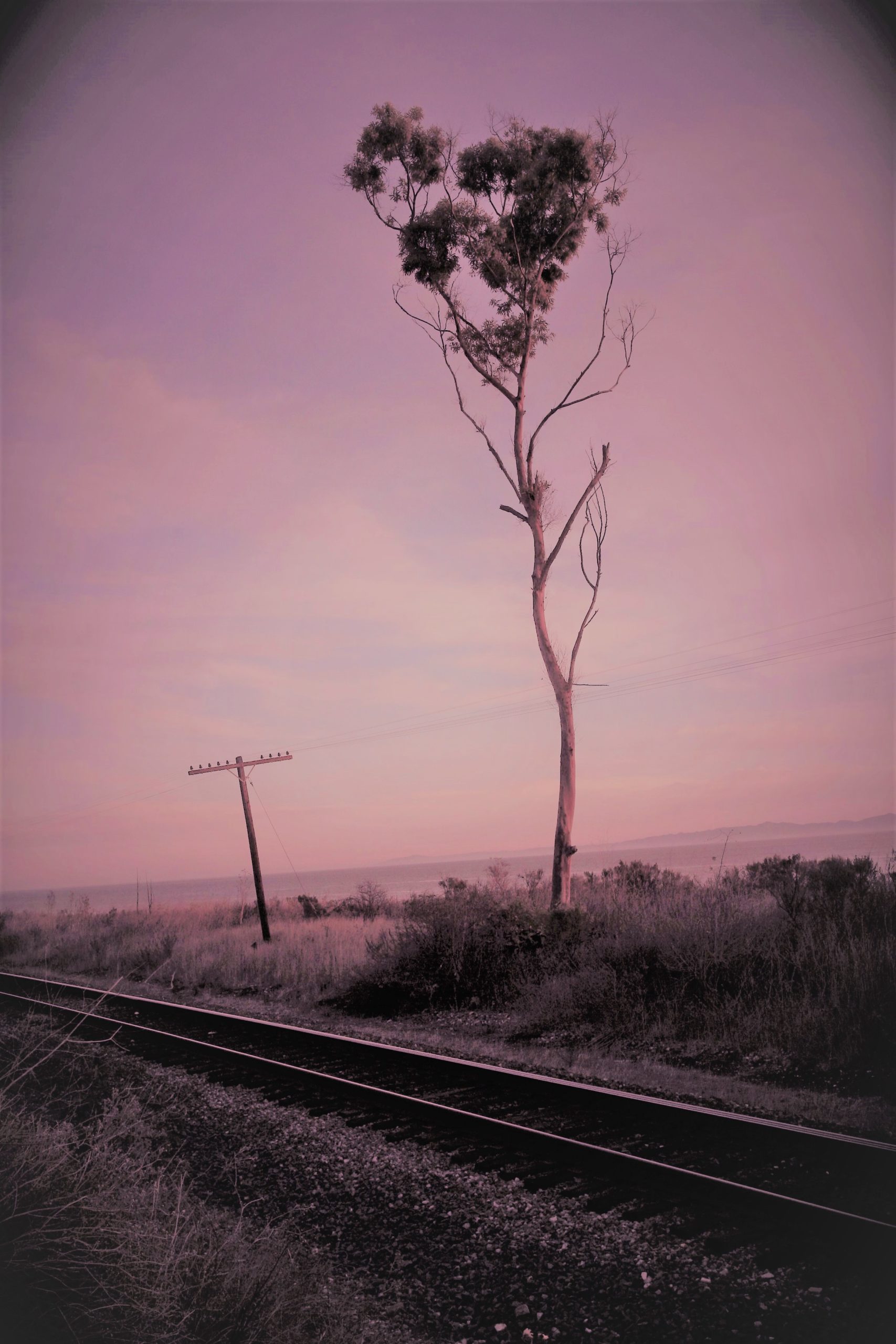

This Moment In Time: Photographs 2007-2017

Fine Art Photography Project 2007-2017

In the wake of Hurricane Katrina’s devastation of New Orleans in 2005, I felt we were entering a critical moment in time – for the world, our work, and myself. It was just an intuition, but one that I felt keenly. With a digital camera at my side for the first time, I decided to act on my intuition and make this moment the subject of an art project.

“When I set out on this project in 2007, I also wanted to capture small and fleeting moments in time, not just the big stuff. Above all, I wanted to enjoy the places I visited and savor the moments as much as possible. I knew they wouldn’t come again. It is my hope that the images collected here are as infused with the joy and zest for the world that I experienced as I traveled and worked as they are with any commentary. It was an extraordinary period of time. Hopefully, I’ve been able to convey a piece of it here.” – from the Introduction

The Sun: a Mystery

Novel set in 2008-09 (Early Hour Press 2018)

A murdered ranch employee. A vanished suspect. A stolen rodeo horse. A black helicopter. Angry environmentalists. Menacing oil-and-gas developers. A Sasquatch hunter gone astray. A mysterious billionaire. A missing can opener…

Without warning, Dr. Bryce Miller, a young doctor in Boston, inherits a large, historic ranch in northern New Mexico from a wealthy uncle she barely knew. She flies out to sell The Sun to the highest bidder, but things get complicated when a body is found murdered on the ranch. Is it a warning meant for her? Meanwhile, she must choose among a colorful cast of suitors who want to turn the working cattle ranch into either: an upscale housing development with golf courses, an oil-and-gas field, a nature preserve, a casino resort, the underground home for a doomsday cult, or the plaything of a shadowy business mogul. Each is willing to pay a large sum of money – and maybe do anything – to get the ranch. Bryce has seven days to decide.

“I am not at all a mystery reader, but I absolutely loved The Sun and I can’t think of a better person than Courtney White to tell this tale of the New West. The Sun is a true page turner and very informative about ranching and the West whether you live in the region or hope to visit. A very engrossing read, indeed!” – Deborah Madison, author of In My Kitchen and Vegetable Literacy

Consilience

Novel set in 2016 to be published

Daniel notices a young woman behaving oddly in an upscale grocery store where she marvels at the bounty of food for sale. Thinking she must be a spy for a foreign government because of the high-tech watch she wears, he strikes up a conversation with her that changes his life utterly. Jo is a spy, but not the usual kind. She is a time traveler on a one-way mission to record information desperately needed in the future, employing technology – and special powers – that don’t exist yet, as Daniel discovers.

Though Jo won’t divulge details, things have gone badly wrong in the future, including politically. She needs his help to complete five Tasks and as they work together, Daniel begins to see our world very differently. Meanwhile, a shadowy group known as The Chasers pursues them as Jo attempts to complete her assignments before her time runs out. Danger and urgency bring Daniel and Jo closer until they fall in love despite the impossibility of their situation. After a brief parting, they become inseparable.

Dirt to Soil

Coauthored Book 2018 (Chelsea Green Press)

Gabe Brown is a pioneering regenerative farmer/rancher in North Dakota. We worked together to get his story into print. The book is a chronicle of the Brown family’s twenty-year journey into regenerative agriculture utilizing cash crops and cover crops with no-till farming integrated with livestock production. It is also an eloquent articulation of the ecological and philosophical principles of regenerative agriculture.

“The Brown Ranch demonstrates that we can be united by our common need for healthy soil. Your body needs nourishment, which means we need healthy food produced from healthy soil—not dirt—which we can accomplish only via biology, not chemistry. If we want to heal divisions, be resilient, and create opportunities for our children then we need to start with soil and work our way up, one plant and one animal at a time. It can be done, as the Browns show, if we set our minds to the task.” – from my Introduction

Fibershed

Coauthored Book 2019 (Chelsea Green Press)

Rebecca Burgess is an author, artist, activist, founder and director of Fibershed, a California-based nonprofit dedicated to regenerative textiles, clothing, and fiber farming. I was honored to be a coauthor on her book.

“This book offers an alternate vision of change, one that focuses on transforming our clothing from the bottom up. It argues that everyone involved in textiles, including grassroots organizers, fashion pundits, investors, and transnational brands, needs to understand that place-based textile sovereignty offers a myriad of globally impactful solutions… Enhancing social, economic, and political opportunities for communities to define and create their fiber and dye systems is key to a new global textile re-design process.” – Rebecca from her Introduction

Regeneration

Coauthored Book 2021 (Penguin)

Paul Hawken hired me as Senior Writer on the sequel to his landmark book Drawdown, which detailed more than a hundred practical solutions to climate change. Regeneration expands his vision to encompass a a regenerative world at every level.

“Paul describes the most important solutions to the environmental and social problems we have brought upon ourselves, and shows how they are inseparably linked. Regeneration is honest and informative, a rebuttal to doomsayers who believe it is too late. He echoes my sincere belief that we have a window of time, that there are practical solutions, and that we and all our institutions can initiate and implement them in order to restore life climatic stability and on Earth.” – Jane Goodall from her Introduction

The Great Regeneration

Coauthored Book 2023 (Chelsea Green Press)

I had the honor of working with Dorn Cox, a visionary leader in carbon farming, open-source networking, and public science. The goal of the book is to explore an emerging commons of ecologically-informed farmers and ranchers who use pragmatic idealism and new technology to bridge urban-rural divides and create a regenerative agriculture that is networked, civically engaged and transformative.

“The advent of the Information Age reveals a radical alternative for human potential – a vision not of the earth as an industrial spaceship with fixed stores of food and fuel in the hold but as a living ecosystem based on the regenerative recycling potential of life. This alternative sees humans as a beneficial species working by informed action presents a unique opportunity to reclaim the purpose of science and agriculture as a shared human endeavor.” – Dorn Cox